The tradition of natural dyes

The practice of using natural dyes has been a tradition for centuries with natural dye sources and methods varying across different regions of the world. In developing the eucalypt dye catalogue, I have blended the ancient practices of my own Lao cultural heritage in weaving and dyeing with the native flora of Australia. Indigenous Australian communities hold deep knowledge of the land and natural dye techniques, such as using ochres and tannins. Both Aboriginal and Lao cultures share a deep connection to their land, viewing dyes not only as colouring agents but also as sources of sustenance and healing.

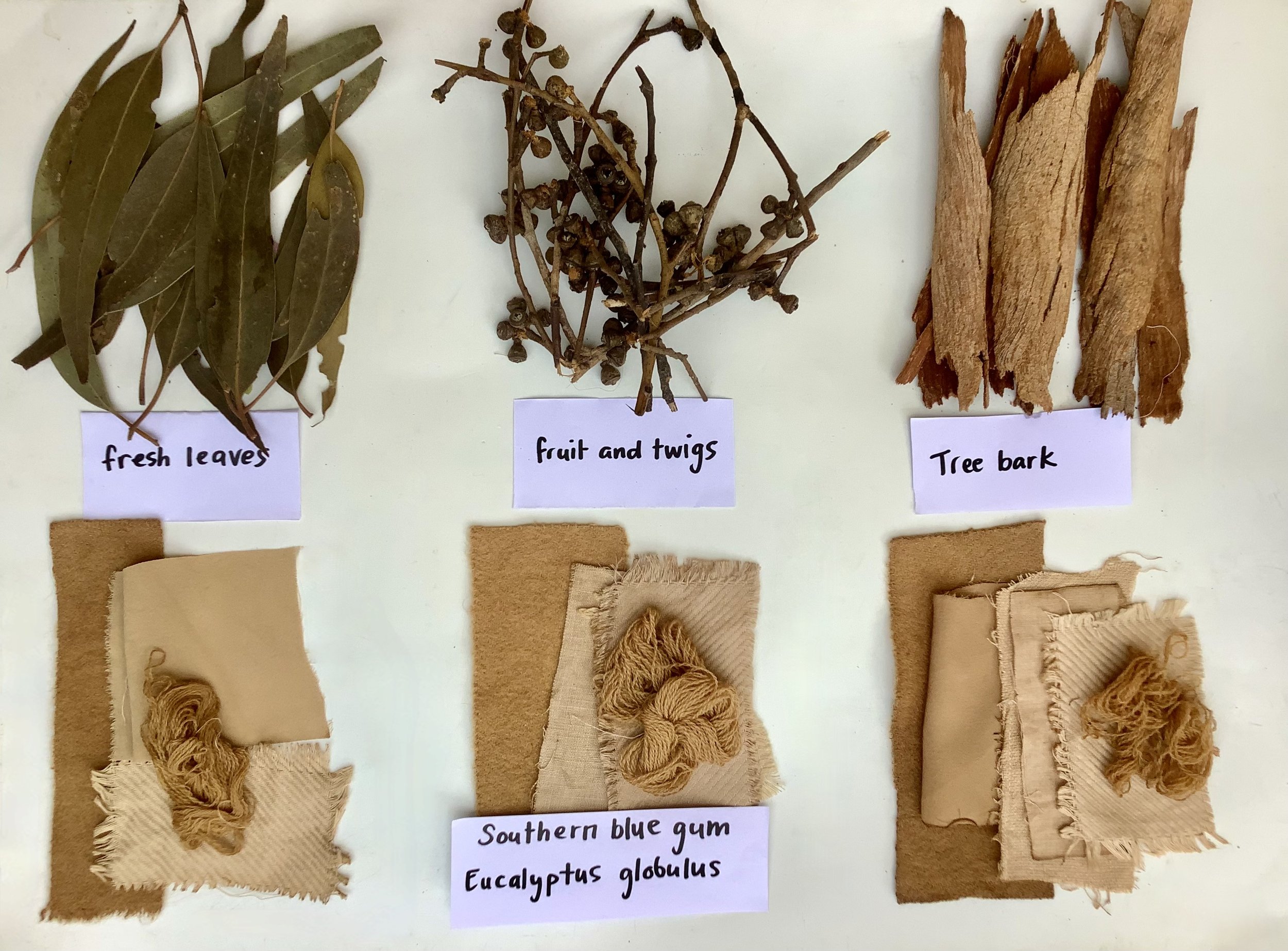

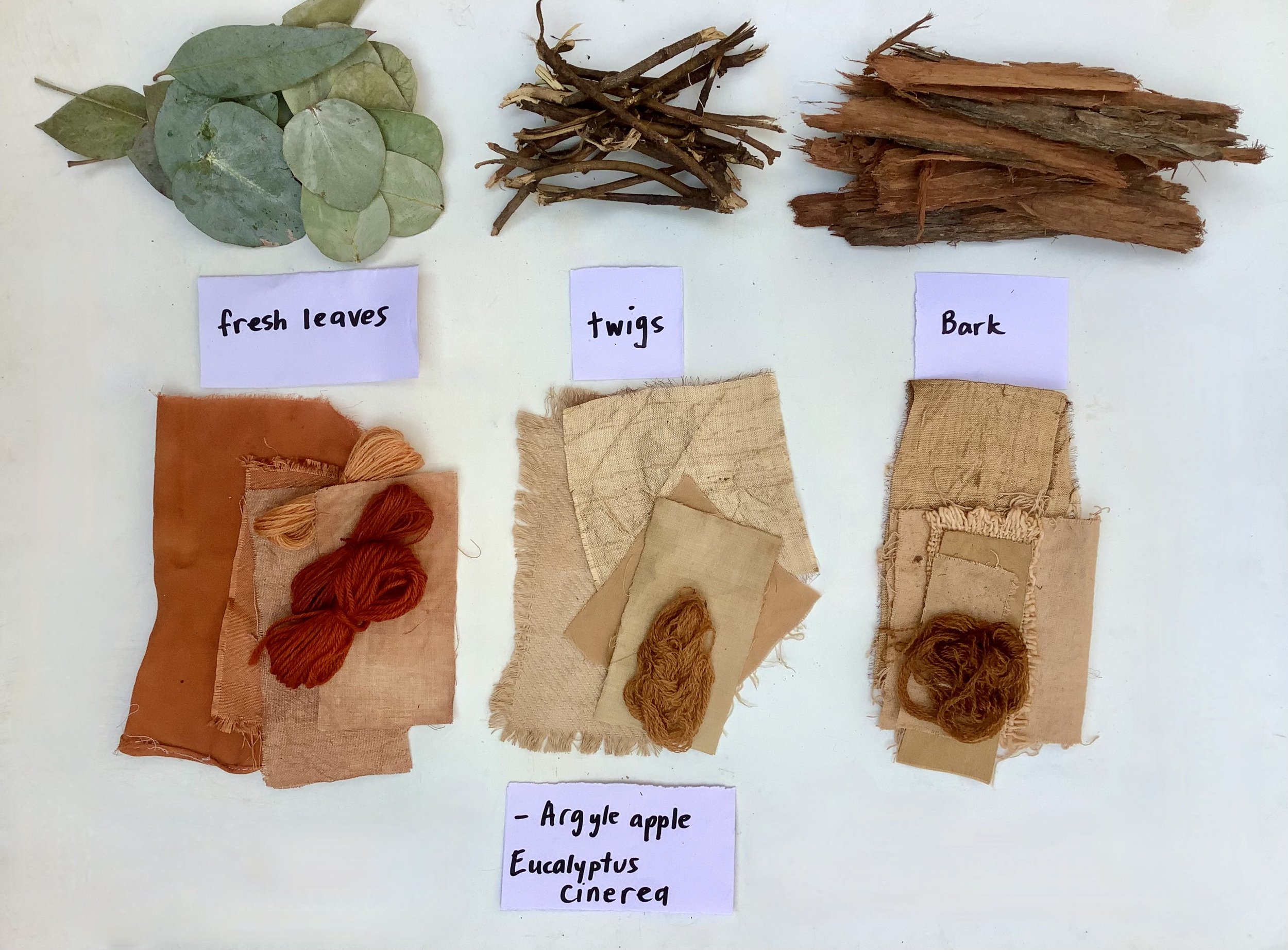

To create the eucalypt dye catalogue, I compared samples of fresh and dried leaves. While fresh leaves may not always be accessible, dried leaves can be stored for extended periods, years. Every part of the eucalypt tree, from bark to seeds to twigs, can be used for dyeing purposes. A few image samples can be seen in the results gallery below.

Prior to beginning my research, I carefully considered the implications of my findings on my final work. My dyeing practice is centred on using locally-sourced, seasonal materials in a sustainable manner. Drawing inspiration from cultures like the Lao and Aboriginal Australians, who have a profound respect for the environment, I prioritise using natural resources available to me. Australia's diverse climates offer a wealth of plant options similar to those found in Southeast Asia, allowing me to blend traditions from both regions in my study. Plants like Moringa olifera and Senna siamea, known for their nutritional and medicinal properties, are rich in tannins and iron levels, making them valuable pre-mordants for my fabrics.

In promoting a philosophy of utilising readily available resources, I seek to honour the ancient traditions and practices of the cultures that have shaped my approach to dyeing.

Fabric selection

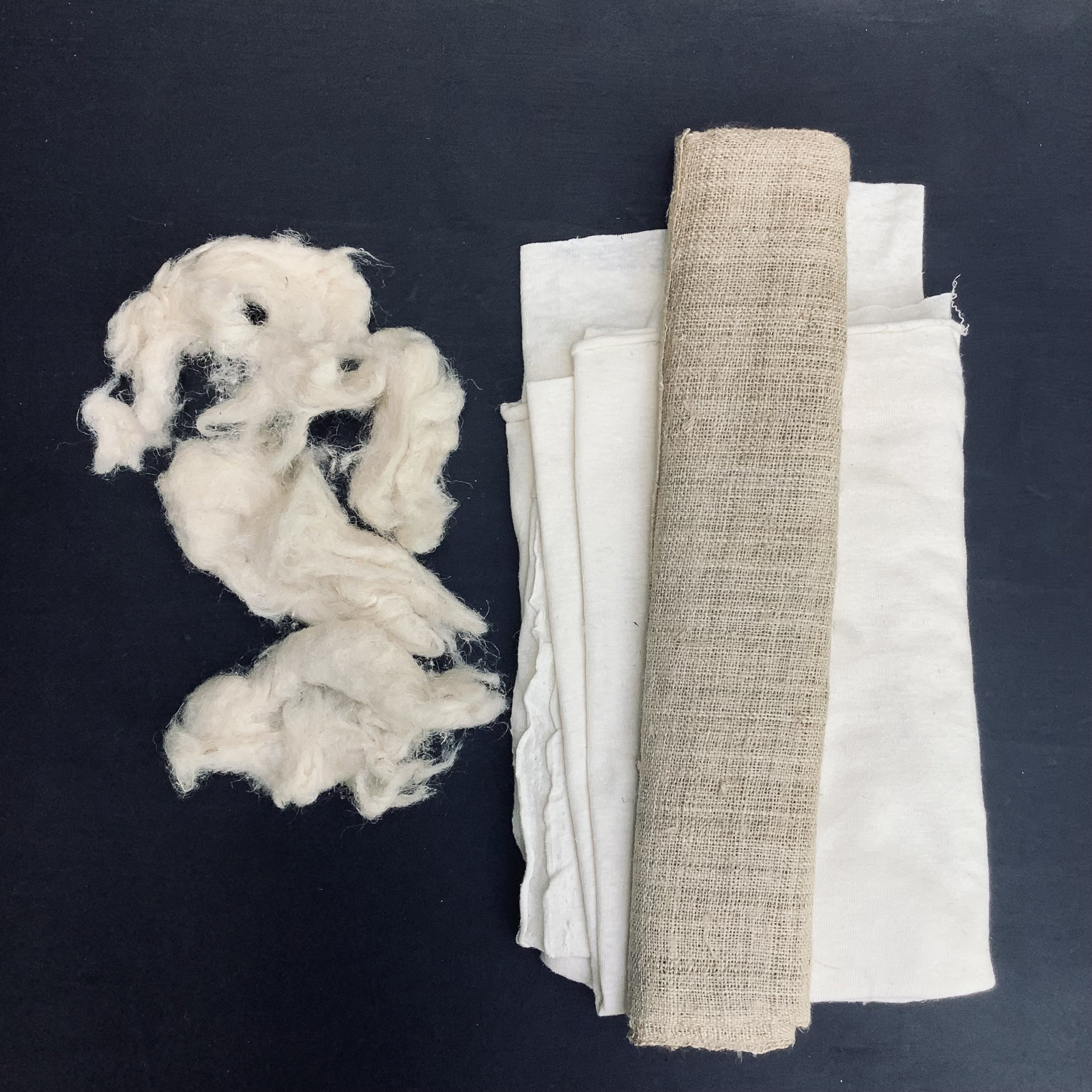

For the dye catalogue, I chose to use hemp, silk and merino wool. The Australian merino wool is some of the finest in the world. The raw fleece was sourced in each state when possible to support local business and mills including North east Yarns. Merino wool blankets were sourced from Waverley Mills in Tasmania and cut into rectangles. The silk is my own handwoven Lao silk. I chose hemp for its durability and was sourced from The South Pacific Hemp Store in Canberra. In some cases where I had access, alpaca wool, lambswool, cotton, linen and silk velvet were also used. The raw cotton was harvested with Grace Dungey in Derby, Western Australia.

Protein vs cellulose fibres

To achieve consistent and even colour in fabric, it is best to dye yarn and thread before weaving. Different types of fibres, like those from animals (protein fibres) and plants (cellulose fibres) require different dyeing methods. Protein fibres, like wool and silk, naturally absorb dye, while cellulose fibres, like cotton and linen, need a mordant (a fixer of colour) to help the dye stick.

Pretreatment of fabric for dyeing

In conducting my research, I chose traditional natural dyeing techniques still used by Lao weavers today, utilising only plant-based mordants and tannins. These methods are both sustainable and readily available, as they rely on local and seasonal plant materials. My aim was to tap into local knowledge and resources without the need to purchase new materials.

I did not use a mordant for either merino wool or silk, as these protein fibres naturally absorb pigment. Prior to dyeing, I carefully scoured the wool and washed the silk with an eco-friendly detergent. For hemp and other cellulose fibres, I used tannins found at each location, specifically opting for Acacia (wattle seed pods). Acacia plants boast some of the highest tannin content in the plant kingdom, with many species native to Australia, abundant throughout the country. Many of the tropical dye plants I worked with in Laos can also be found in tropical regions of Australia.

For the Queensland part of my research I used Senna siamea (also known as Cassia senna) harvested from my parents garden in Southwest Brisbane. It is known for its immune-boosting properties and has been used to treat various health conditions. The leaves, pods, and seeds of the Senna tree are edible and contain essential nutrients, but should be properly prepared before consumption due to potential toxicants. The leaves are also used in Southeast Asian cuisine. Tannin can be found in all parts of the tree with up to 17% in the leaves. The local name in Lao and Thai is Khi-lek. Studies of the leaves have identified they are a good source of essential nutrients in it contains protein, fibre, fats and minerals (iron, magnesium, copper, potassium, manganese and lead).

The Acacia seed pods and tannin used for each state:

ACT - Acacia rubida

NSW - Acacia decurrans

Queensland - Senna siamea

South Australia - Acacia montana

Tasmania - Acacia dealbata and Acacia rubida

Victoria - Acacia rubida

Western Australia - (Southwest WA) Acacia leioderma and (Broome) - Acacia coleii

Eucalypt dyeing process

The dyeing method used for my eucalypt catalogue was kept simple in order for it to be easily replicated.

Most the dyeing was done on location. Rainwater was used if it was available otherwise I used scheme (tap) water.

Dye Bath Preparation

1 - 100 grams of fresh leaves were weighed and rinsed in water.

2 - The leaves placed into a stainless pot and filled with three litres of water.

3 - The lid is placed on and the pot is brought to boiling.

4 - Once the pot with leaves began to boil, it was turned down to 75 percent and left to boil for one and half hours.

If needed, water was added to make sure the leaves always remained submerged.

5 - The dye liquid was then equally poured into three smaller pots and the fabric swatches of silk, wool and hemp were placed in each pot.

6 - The pot was brought back to the boil and turned down to 50 percent heat for a further one hour to reach the optimum colour.

The same process was used for the dry eucalypt leaves. The leaves were then removed, rinsed off in a bucket of plain water and left to dry.

Results

Most of the dyeing of the leaves was done on location. The size of the fabric samples were irregular. This was a result of several factors, firstly, it was not certain how many species I would be able to collect at each location, therefore some of the swatches had to be cut down in order to make sure there was enough fabric for all dye samples.

It is possible to achieve a variation of colours depending on amount of leaves, type of fabric and boiling time. The uncontrolled environment was part of the process. Each of the eucalypt samples is the result of 2 hours and 30 minutes of boiling time. Samples can be seen in the Eucalypt Gallery page.

NOTE: Every part of the tree can be used to extract colour, leaves, seeds, twigs and bark that will vary in results. Below you will see samples of fabric dyed using Southern blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus) and the Argyle apple (Eucalyptus cinerea) where leaves, fruit pods, twigs and bark were used to extract colour. The results will vary with each species.

I collected 370 species of fresh and dried leaves. The entire preparation of fabric and dyeing process to produce the eucalyptus colour samples was the result of more than 2200 hours of labour.